What is Young, Talented and Afraid of the Dark?

Communication Arts, January-February 2015

Over the years, I’ve learned that when it comes to riddles, the world is split into two types of people—those who live for a good riddle and those who abhor them.

One particular photography team our firm works with is living proof of this. At any given shoot, half of the team typically shuts down at the mention of a riddle, to the point where they will physically distance themselves from the discussion. As the art director at these shoots, I like to monitor the general mood of the creative team and keep things positive. So introducing riddles doesn’t always work. Some people find these conundrums intimidating and not very much fun at all.

Conversely, riddle lovers welcome the challenge to solve a new mystery. Just the mere mention of a riddle gets the adrenalin flowing. As J.J. Abrams, the accomplished television and movie producer, said, “Mystery demands that you stop and consider—or, at the very least, slow down and discover.”

Recently, our graphic design firm experienced a perplexing situation that exposed some weaknesses in our creative process. This surprised and worried me. The more I thought about this dilemma, the more I wanted to understand what had happened. We had our very own mystery, and I wanted to solve it.

In December 2013, a printer selected us to produce an issue of its monthly magazine, Wayward Arts—working with the theme of “community.” The assignment was extremely open, allowing us to dive into a subject matter of our own choice. After several discussions, we settled on an altogether alluring community: bees. The mention of beehives, beekeepers, honey hunters, hexagons, pollination, migration, heraldry and colony collapse— none of which we knew much about—genuinely excited us. The project proved to be a welcome diversion from our other work and kept us immersed in “all things bees” for the next four months.

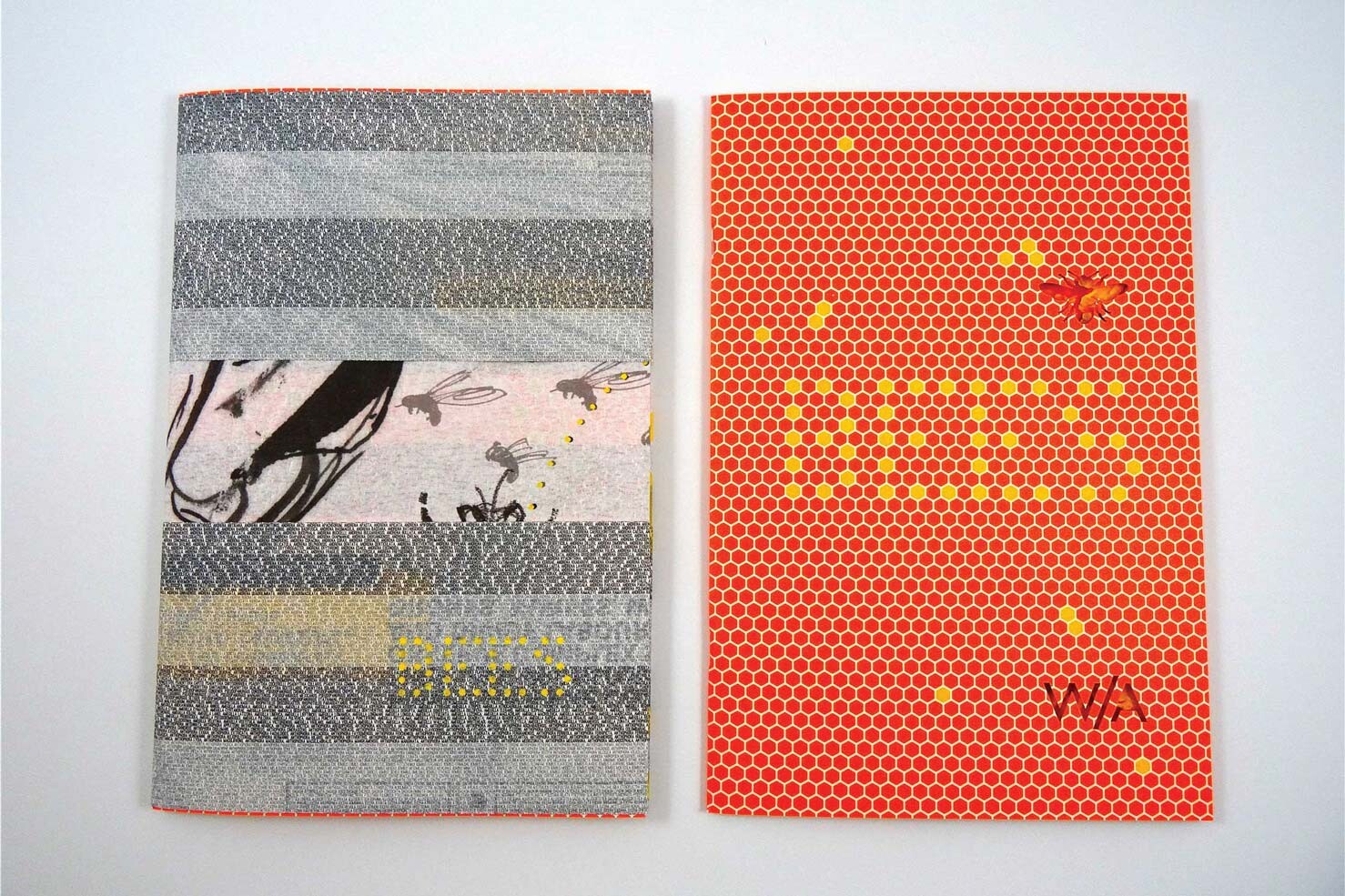

The result was Bees, a 34-page publication showcasing various printing techniques, from laser cutting and silk screening to metallic and fluorescent inks. We were sitting on so much research that we also produced a one-page website called the Beeswax for those viewers interested in learning more about these busy creatures.

So where’s the dilemma? What’s the mystery?

The seasoned designers in our studio fully recognized that an opportunity with this amount of creative freedom doesn’t come around very often. Their enthusiasm was palpable. Yet throughout the design process, they observed that the junior designers seemed far less invested in the project. They were shying away from discussions, were hesitant to contribute ideas and lacked an overall curiosity for the subject matter. Coincidentally, another design firm creating a Wayward Arts issue experienced the exact same problem—lackadaisical junior designers. And like me, they found this troubling.

I spent many hours pondering this mystery. Like a tape loop, the Bees design process played over and over in my mind. Where did things go wrong? We had been very open-minded in our design process—encouraging participation, discussion and ideas. We made ample time and resources available to all. It was when I reviewed notes from talks on curiosity I’ve given at design schools and conferences that I remembered research that provides an important clue. Studies have shown that a well-developed sense of curiosity nurtures other valuable qualities in young people, such as open-mindedness, persistence and innovation. There, at the bottom of my notes, I’d written a phrase that was key: “tolerance for ambiguity.”

Having a tolerance for ambiguity means being able to feel comfortable even when things are unresolved. You may not know where you are heading, but you realize that uncertainty is part of the process. Paul Sloane, author of the book How to Be a Brilliant Thinker, has the following to say about the subject: “Routine thinkers are often dogmatic. They see a clear route forward and they want to follow it. … they will likely follow the most obvious idea and not consider creative, complex or controversial choices.”

Tolerance for ambiguity is not a trait we are born with, it is something we learn over time, through experience in ultimately solving problems successfully. The senior designers in our studio had years of practicing this skill and use it intuitively on a daily basis. We assumed all designers worked the same way. What we didn’t take into account is that this skill is underdeveloped, possibly nonexistent, in most junior designers.

Now that the mystery was solved, what next? How do you go about teaching someone to tolerate ambiguity and even relish the “not knowing” state before the riddle is solved? Can it even be taught? I believe so.

It starts with how managers can help. Designers need time to absorb things, to explore a range of possibilities and to cultivate their ideas. Start by providing a thorough design brief so they have the necessary details to fully grasp the assignment. I’m not a big fan of group brainstorming sessions where others can influence and inhibit one’s thought process. They’ll be ready to discuss their ideas once they’ve had adequate time to do their own conceptualizing.

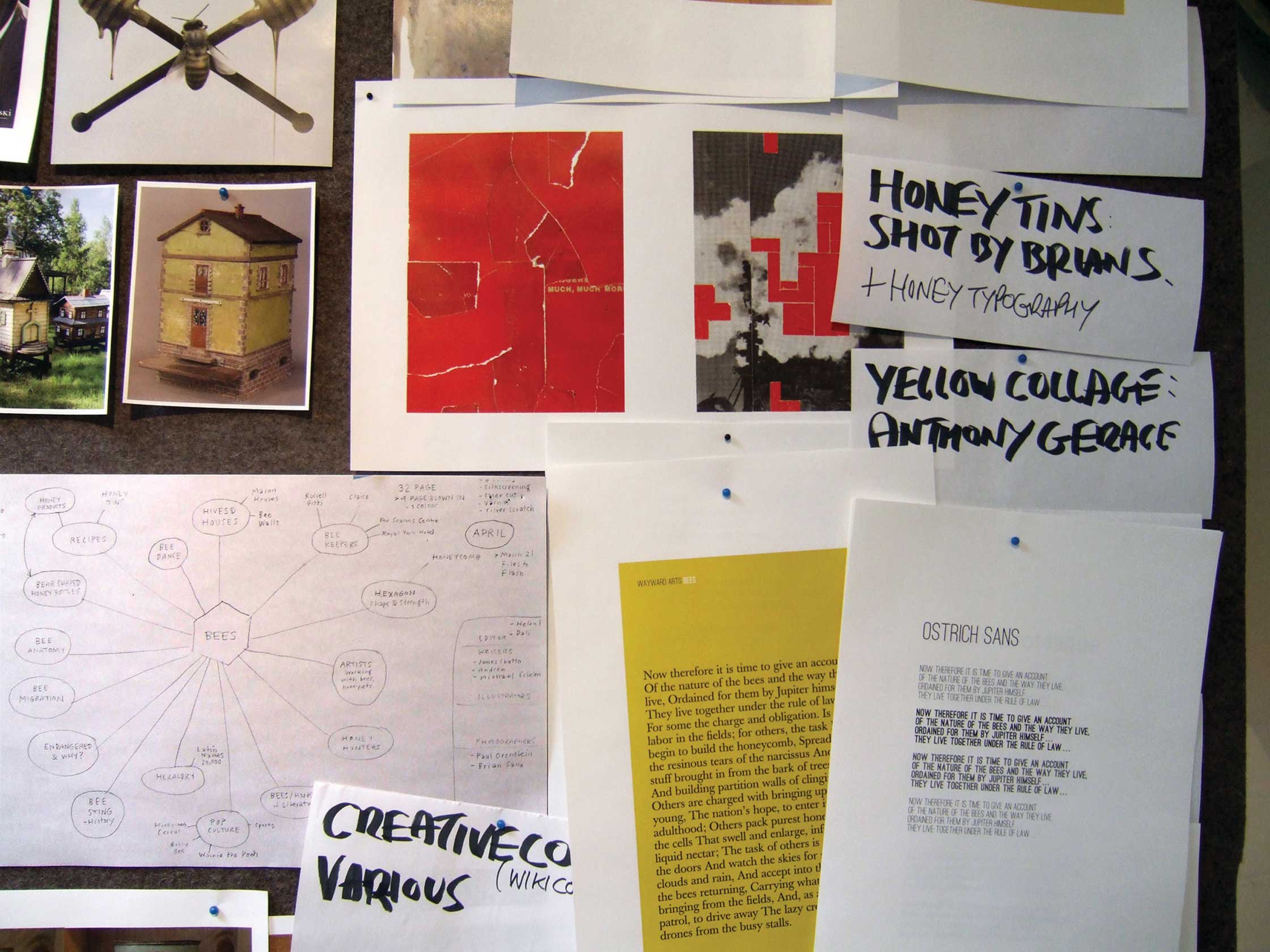

It’s imperative that you make creatives comfortable with the idea of sharing their findings. Establish in-studio project boards, Pinterest boards, white walls and the like so that others can see what you’ve discovered. Collections of images and ideas can initiate provocative discussions and uncover fresh avenues to explore. Be mindful of what others add to the mix and stay receptive to their contributions and comments. Explaining and defending your ideas will help verify your commitment to them.

Help designers get used to the fact that feeling unsettled is good. During the exploratory phase, they should remain impartial to all that they discover. Keep group meetings open and positive—no room for naysayers. Remind everyone to take time to digest and contemplate ideas that at first seem outside their comfort zone. Like archeologists, keep digging for more. You can start to make sense of the findings once it’s all unearthed. Don’t be intimidated by the confusion; with time and consideration, the pieces will start to fall into place.

As visual people, designers can help themselves become more comfortable with the exploratory phase by creating pictures of their thought processes and ideas. Mind mapping enables you to document your investigations and expose unforeseen connections. There are a variety of ways to mind map—using words only, incorporating images and sketches, purchasing a mind-mapping software program. Take the time to create a style you are comfort-able with. Your ideas need to reside somewhere other than inside your head. Let them out.

Most important, stay flexible. Ideas are meant to change and evolve—nothing is written in stone. Consider fresh viewpoints, multiple viewpoints and opposing viewpoints. See where they lead you. The creative process is about curiosity and discovery. Remaining flexible is ultimately a sign of confidence—confidence to know when your ideas are strong and to admit when they are weak.

Developing a tolerance for ambiguity is, at its core, a personal undertaking. However, there are external factors that impact its growth. It helps to be in the company of designers, art directors and creative directors who value its importance. And working in an open-minded environment, where your ideas are encouraged and respected, makes a big impact. Improving this skill takes time, but it’s an investment worth making, for all involved.

Canadian book publisher Robert Fitzhenry may have put it best when he said, “Uncertainty and mystery are energies of life. Don’t let them scare you unduly, for they keep boredom at bay and spark creativity.” You can wait for a person to tell you the answer to a riddle, but wouldn’t you rather experience the satisfaction of deciphering it on your own?