What Fuels Innovation?

Applied Arts, July 2012

Curiosity. If “innovation” is the new mantra of business, then we must learn to nurture curiosity and creativity at an early age.

Innovation. You read about it everywhere these days.

It appears that the business world, in an effort to champion innovation, is distancing itself from its recent fascination: design thinking.

Fortunately, innovation and design thinking have one crucial thing in common: creativity. The problem is that creativity can be just as nebulous a construct to grasp as design innovation. But there is a vital component to creativity that is easy to access: curiosity. So now that innovation is the new mantra of business, it is curiosity that must be encouraged.

Advertising guru Leo Burnett once said, “Curiosity about life in all of its aspects, I think, is still the secret of great creative people.”

Although we are all born with an acute sense of curiosity, it evolves in each of us in different ways. For the majority, curiosity will flourish while we are very young and in the care of our parents, who will try to answer our incessant queries. Once we start school, it is a different story. The intimate one-on-one relationship we had at home is replaced by a new dynamic, one which doesn’t yield the level of attention to which we were accustomed. No matter how good the school and teachers, our individual curiosity will take a backseat to the needs of the collective whole. Studies have shown that most people’s sense of curiosity peaks by age five!

Those who pursue a post-secondary education in art, design, architecture, science and the like, will find that studio-based classes emphasize exploration, experimentation and prototyping, which, in turn, rekindle one’s sense of curiosity. Here one learns what I call the five tenets of curiosity: observation, inquiry, challenge, exploration and risk-taking.

If curiosity leads to creativity, and creativity leads to innovation, then it makes sense that we can teach people to be innovative. We need to start this process with young children, while their sense of curiosity is still alive. We can give them the tools they need to make them more innovative in whatever they pursue later, whether it is art, design, science, law, business, politics, etc.

During the 2010 Design Thinkers conference in Toronto, I asked Christopher Chapman, the global creativity & innovation director at The Walt Disney Company, what had spurred his curiosity when he was young. He immediately cited the one-hour-a-week Creative Learning Resource (CLR) class he took in elementary school, in Chicago. It focused on individual and team projects, the kind that had no right or wrong solution, but encouraged discussion, exploration and experimentation. He recalled fondly the challenge of constructing a bridge out of just Popsicle sticks and glue. That one class, he says, established a way of problem solving that has stayed with him ever since.

There is also much to be learned from the Montessori system and its unique approach to education. It places a high value on curiosity and “seeks to develop children into naturally curious young adults through self-guided learning.” Our elementary school curricula are already heavy with courses that demand either right or wrong answers. Why can’t there be a one-hour-a-week class that is built around the concept of “what-if” answers? A class that promotes inventive solutions to problems and rewards a student’s willingness to try. A class where curiosity is embraced, nurtured and championed.

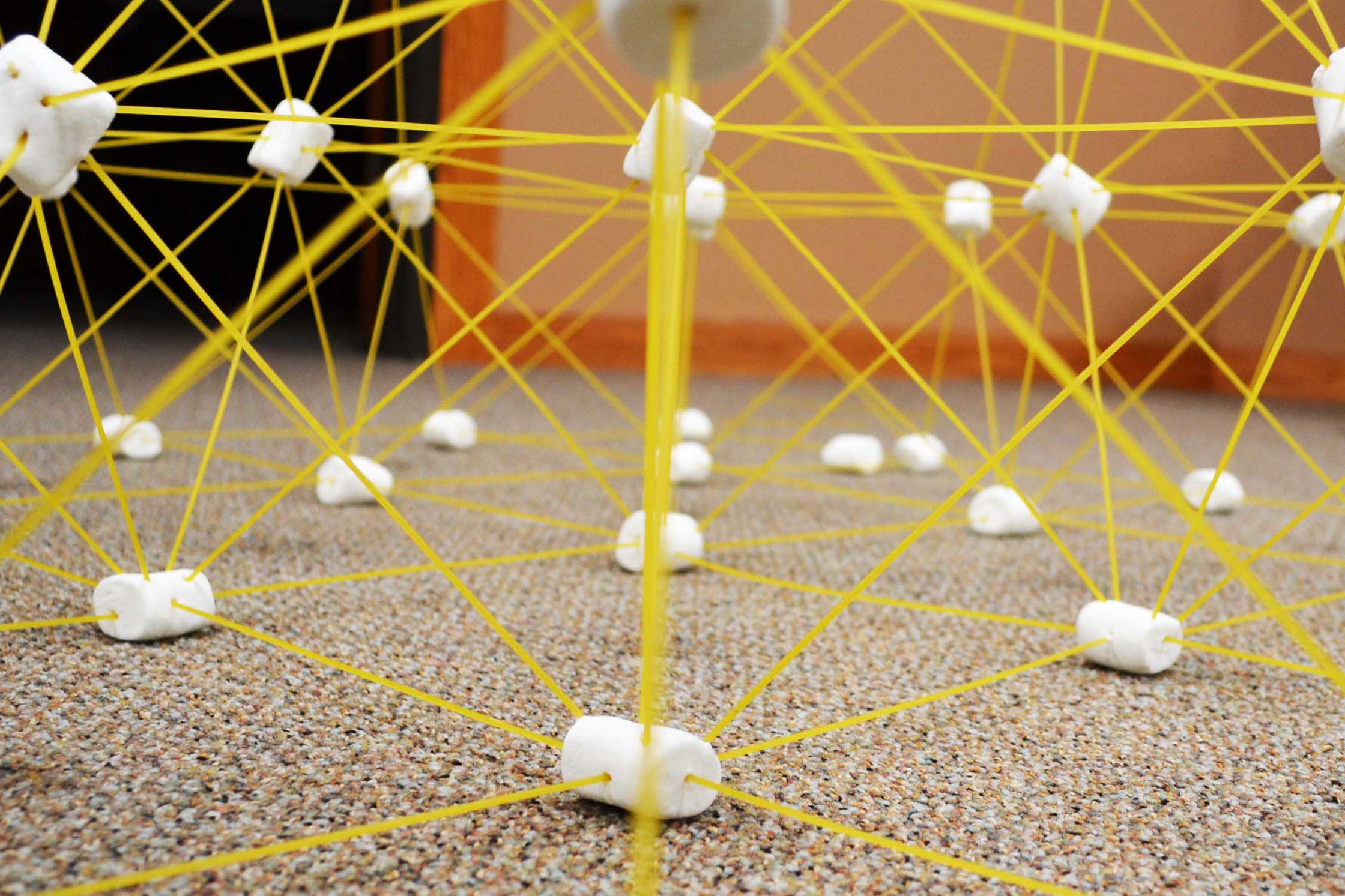

A team-building exercise called “The Marshmallow Challenge” is currently making the rounds. Teams have 20 minutes to construct a tower using just one metre of tape, one metre of string and 20 pieces of dry spaghetti. The completed tower must support a marshmallow. Results show that after architects and engineers, that it is the kindergarten students who build the tallest towers—not to mention, the most interesting structures. And it is business students who consistently produce the worst results.

Unfortunately, most people are afraid that curiosity will make them look stupid. It’s much easier to pretend you know what’s going on than it is to admit ignorance. Being curious also means taking risks. Sometimes we are successful and sometimes we fail. Most people are wired to be fearful of failure from a very young age.

In a study conducted by the University of Colorado business school in 2010, researchers found that “the knowledge gained from success was often fleeting, while knowledge gained from failure stuck around for years.” Young people need to know that mistakes are part of the process of learning. Curiosity is a sign not of weakness but open-mindedness. Psychologists believe that a curious child also possesses superior intelligence, creativity, reliability, responsibility and, my favourite, tolerance for ambiguity.

Innovation, I believe, is the right thing for business to be focused on—especially now. Competition is fierce. Economic problems have arisen due to the fact that we ignored the critical imperative for constant improvement. So when we think of innovation and creativity, remember the role that curiosity plays in this equation. And remember that it lives inside all of us.