Collective Behaviour

Applied Arts Magazine, September-October 2013

I experienced something on the internet recently that I’m convinced has its origins in a little-known 16th century phenomenon.

Many years ago, while touring Scotland with my wife, we happened upon a castle nestled in the rugged highlands north of Inverness. There, perched atop a cliff towering over the shores of the North Sea, was the majestic Dunrobin Castle, home to the clan Sutherland. This handsome estate, dating back to the 14th century, boasts conical turrets, a clock tower and a formal French garden complete with topiaries and giant rhubarb. Despite all the grandeur, what intrigued me most was a modest stone structure bordering the west end of the garden. Sitting alone, like a neglected child, this humble building appeared at odds with its surroundings. I was immediately attracted to it.

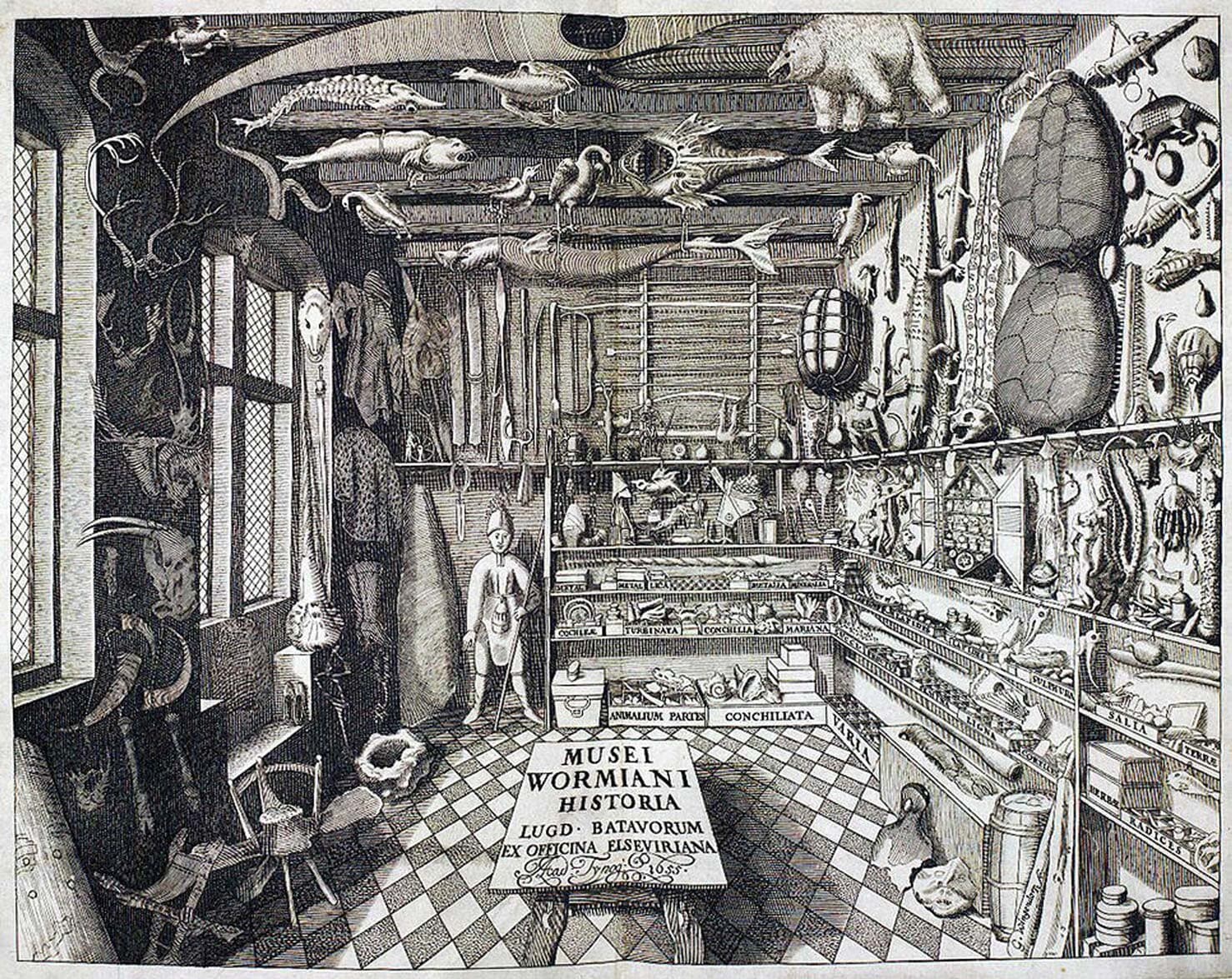

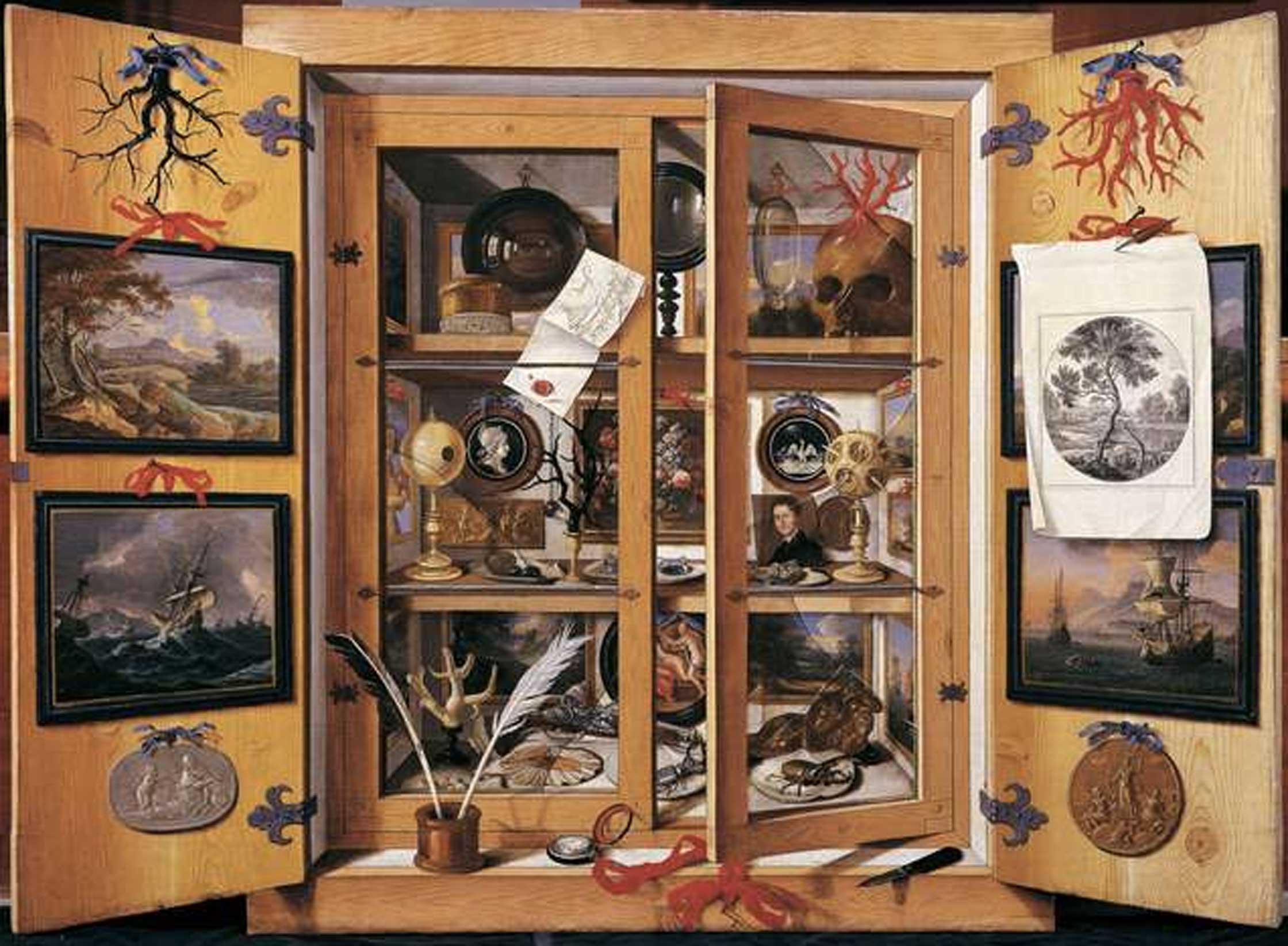

I ventured up its weathered steps and entered through a simple wooden door. Before me was a sight that I will never forget – staring me directly in the eyes was the head of a stuffed giraffe truncated at the bottom of its six foot neck. As if that wasn’t enough of a shock, the wall behind the giraffe was chock-a-block with animal trophy heads – wildebeest, antelope, water buffalo and elephants. Tails, tusks and antlers of all shapes and sizes adorned the remaining walls. Guarding the corner, sitting on its hind legs, was an alligator with its menacing mouth wide open. On the floor was an eerie looking pair of elephant feet. It was overwhelming and I was transfixed. The adjoining room had three levels and was supported by a network of sturdy wooden beams. The afternoon sun, filling the room with a honey glow, illuminated dusty display cases of natural treasures. Cabinets of shells and fossils led to displays of songbirds and small mammals. Larger geological specimens and carved stones peppered the floor. Upstairs were seven expansive glass cases, one for each of the continents. Objets d’art, keepsakes and textiles crowded their shelves.

I had stumbled into the Sutherland clan’s cabinet of curiosities, or what the Germans so aptly call the Wunderkammer – the wonder room! This collection represented the exploits of generations of Sutherlands. Housed in this building were artifacts, flora and fauna and curiosities of all descriptions acquired by the family over many years.

Cabinets of curiosities can be traced back to the 16th century when those of great wealth and power (such as royalty and the aristocracy) accumulated magnificent examples of the rare and unusual. In their quest for knowledge and understanding, they combed the globe for new discoveries. Over time, cabinets of curiosities became more popular. Scholars and scientists used them to express both their sources of inspiration and their intellectual sophistication. Patrick Mauries, in his book Cabinets of Curiosities explains, “Display panels, cabinets, cases and drawers were a response not only to a desire to preserve or conceal from view, but also to slot each item into its place in a vast network of meanings and correspondences.” In the course of time cabinets of curiosities became less private and more public, forming the foundation for our very first museums.

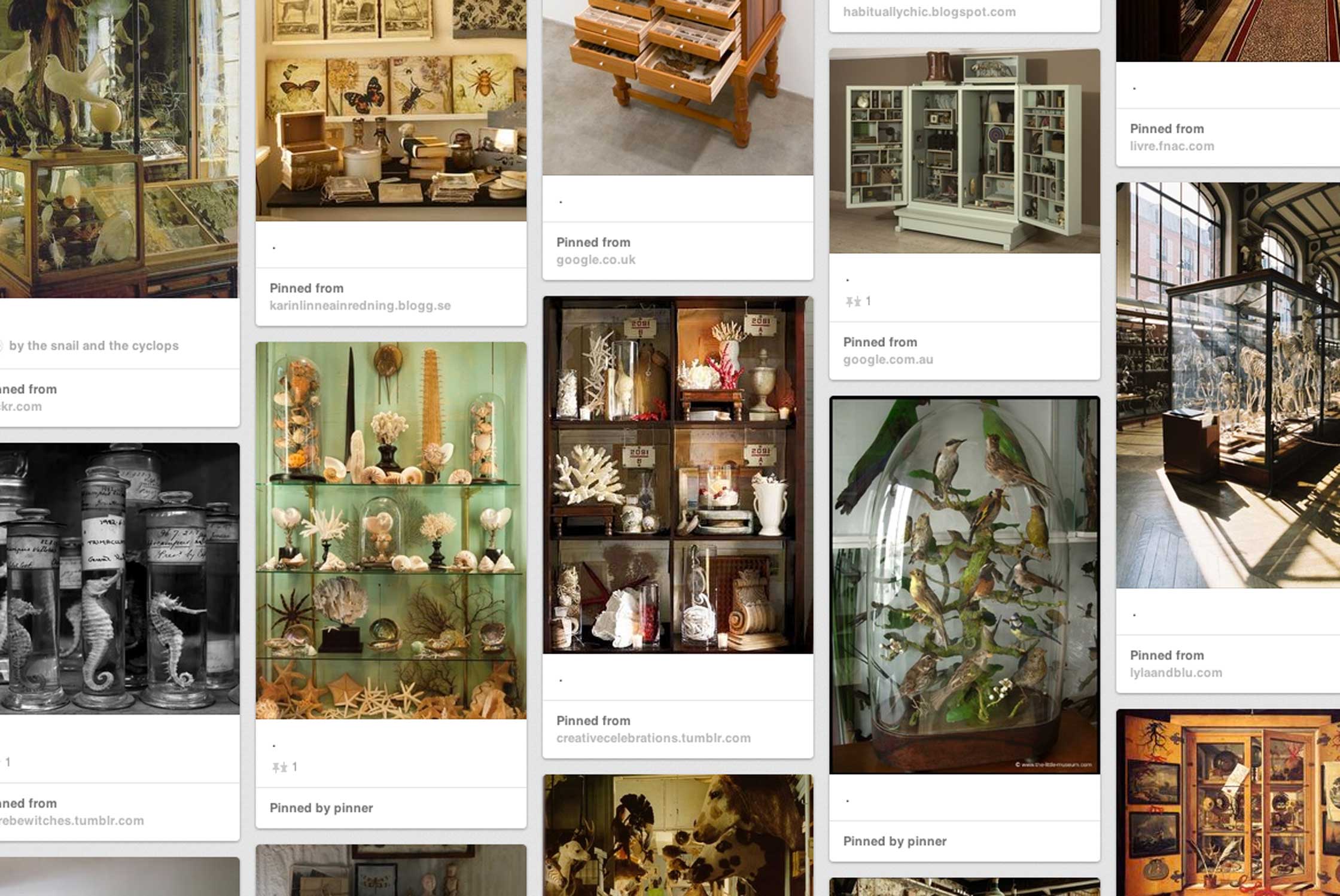

Dunrobin Castle’s Wunderkammen came to mind when I first experienced the latest online craze – Pinterest. Myself and several of my colleagues have our own Pinterest sites whereupon we earnestly collect, post and share curiosities. These pages become extensions of ourselves, our interests and our desires. As the popular website boasts, “Pinterest lets you organize and share all the beautiful things you find on the web.” They have made it remarkably easy to create online cabinets of curiosities – especially now that money has been eliminated from the collecting equation. These pages say more about who we really are than do our other on-line collections – the ones listing our friends and business associates. Pinterest enables us to exhibit the many influences that, like our clothing and our homes, help fashion our personalities.

People have always been compelled to collect. Collecting satisfies a variety of needs – it connects us to the past, it sends us on quests and, at its source, helps to define us as individuals. Collecting is also a way of stimulating creativity by keeping us observant and inquisitive. In their 2011 article in Psychology Today magazine, Robert & Michele Root-Bernstein put it best when they said, “…making a collection can provide the intellectual and sensual stimulation necessary to inspire your personal creativity. As with much creative endeavor, the key is to use collecting to develop skills and knowledge, and then to propel you from what you know to what you do not.”

Psychologists believe that collecting, in part, enables us to develop our own personal havens of familiarity. We can retreat to our collections for comfort anytime we find the need to calm our fears or insecurities. Pinterest is the place where we can now create our very own havens.

Today Dunrobin Castle refers to its Wunderkammen as a “museum.” Thankfully we still have museums, as nothing can quite match the experience of seeing an object in person. As the world gets smaller and the World Wide Web gets larger, it is the internet where we now do our collecting. The modern cabinet of curiosity is virtual and virtually limitless. It is portable, inexpensive and easily shared. And like its predecessors, it keeps us connected to the world, keeps us informed and keeps us hungry for more.